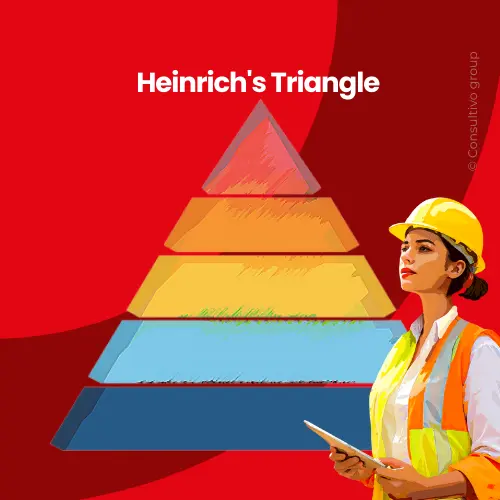

Heinrich’s Triangle or a Safety Triangle shows that major accidents rarely happen in isolation. For every serious incident, many minor accidents, near misses, and unsafe behaviours typically occur beforehand. This relationship explains why tackling small issues early is one of the most effective ways to prevent catastrophic events.

By analysing deep into Heinrich pyramid of safety, organisations can unlock invaluable insights that not only enhance workplace safety but also promote a culture of proactive risk management.

This approach helps shift the safety focus from simply reacting to injuries to actively identifying and eliminating risks long before they can cause harm.

Through comprehensive analysis and actionable strategies, this article will guide you on a journey to better understand how to effectively leverage the Heinrich safety triangle in your safety protocols.

Prepare to empower your team and minimise risks as we explore the dynamic interplay between behaviour, incidents, and prevention in the quest for a safer environment.

Join us as we explore the transformative potential of this vital safety triangle model.

What you will find here

Understanding Heinrich’s Triangle: An Overview

The safety triangle, also known as the Heinrich pyramid theory, is a foundational concept in the realm of safety management. Developed by H.W. Heinrich in the early 20th century, this model serves as a pivotal framework for understanding the relationship between different types of workplace incidents.

At its core, Heinrich’s triangle posits that for every major accident, there are many more minor incidents and even more near misses.

The visual representation of the Heinrich safety triangle is compelling: the base comprises numerous minor mishaps and near-misses, while the apex symbolises a single major accident.

This structure clearly underscores the significance of addressing minor incidents to prevent more serious accidents. By focusing resources on the base of the safety pyramid, organisations can significantly reduce the likelihood of catastrophic events. This proactive approach shifts the emphasis from reactive measures taken after a major incident to preventive strategies that mitigate risks before they can escalate.

Understanding the intricacies of the Heinrich triangle is crucial for developing effective safety protocols. It provides a clear framework for analysing incidents and understanding their underlying causes. Moreover, it emphasises the importance of a systematic approach to safety management, where every minor incident is an opportunity to learn and improve.

As we explore the various components and applications of the Heinrichs triangle, we will uncover the transformative potential of this powerful safety pyramid framework.

The Historical Context of Heinrich’s Triangle

The origins of Heinrich’s triangle can be traced back to the early 1930s when Herbert William Heinrich, an American industrial safety pioneer, conducted extensive research on workplace accidents.

His findings were published in his seminal book, Industrial Accident Prevention: A Scientific Approach, in 1931. Heinrich’s investigations, primarily focused on insurance data, revealed a striking pattern in the occurrence of workplace incidents.

The original Heinrich accident triangle proposed a ratio of 1:29:300. This meant that for every one major accident resulting in a serious injury or fatality, there were approximately 29 minor injuries and 300 no-injury accidents, or near misses. This discovery highlighted the interconnected nature of different types of incidents and the importance of addressing them collectively. It was a revolutionary insight.

Heinrich’s work was groundbreaking for its time, as it shifted the focus from merely responding to accidents to actively preventing them. Prior to his research, safety management primarily involved reacting to incidents after they occurred.

The Heinrich pyramid theory introduced a proactive approach, emphasising that by systematically addressing minor incidents and near misses, organisations could prevent major accidents.

This paradigm shift had a profound impact on the field of safety management.

It laid the groundwork for modern preventive strategies and influenced the development of many behaviour-based safety programmes used today.

The Components of the Safety Pyramid Explained

The original Heinrich pyramid of safety is composed of three distinct layers, each representing different types of workplace incidents. Understanding each component is vital for effective risk management.

Near Misses (The Base in Heinrich’s Triangle)

At the vast base of the accident triangle are the near misses. These are events that could have resulted in an accident but, due to luck or a last-minute correction, did not.

These incidents are often overlooked because they do not cause harm or damage. However, they are critical to understanding the underlying risks and potential hazards in the workplace. They represent critical failures in the system that must be addressed immediately.

By analysing near misses – often captured through employee safety surveys or structured bbs observation – organisations can identify patterns and implement corrective measures to prevent similar incidents from occurring in the future.

The sheer volume of these events means that focusing on this layer offers the highest return on investment for safety resources. A single near miss is a combination of an unsafe act unsafe condition and should be treated as a free lesson.

Minor Accidents (The Middle Layer in Heinrich’s Triangle)

The middle layer of the safety pyramid of Heinrich consists of minor accidents. These are incidents that result in non-fatal injuries (e.g., a cut requiring first aid) or minor property damage. These incidents are more noticeable than near misses and often receive more attention from safety professionals.

However, they are still frequently underreported or inadequately addressed in terms of root cause analysis.

The Heinrich accident pyramid emphasises the importance of thoroughly investigating minor accidents to uncover their root causes and implement effective preventive measures.

By addressing these incidents, organisations can significantly reduce the likelihood of more serious accidents. This layer serves as the clearest statistical indicator of failure that requires action.

Major Accidents (The Apex of Heinrich’s Triangle)

At the apex of the safety triangle are major accidents. These incidents result in severe injuries, fatalities, or significant damage and loss.

These are the most visible events, receiving the most attention from management, regulatory authorities, and the public. However, Heinrich’s triangle clearly illustrates that major accidents are often the culmination of numerous minor incidents and near misses.

By focusing on the base and middle layers, organisations can prevent the escalation of risks and create a safer work environment.

Start your safety culture development journey

The Dynamic Link Between Behaviour and the Accident Triangle

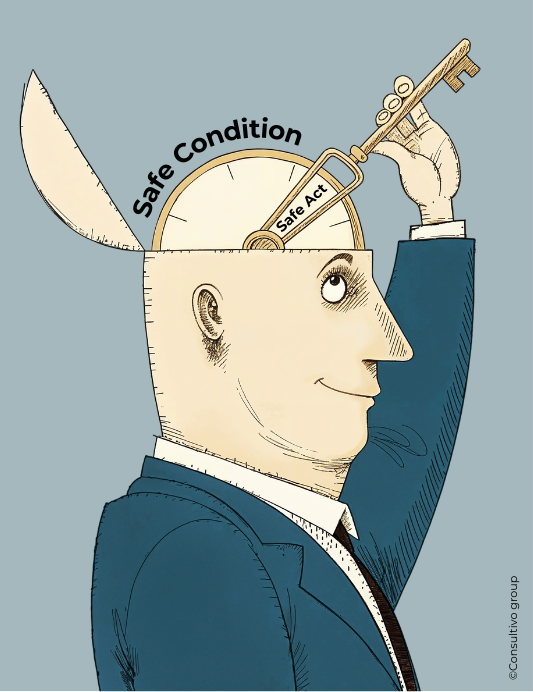

A key component of Heinrich’s original findings was his assertion that a high percentage (up to 88%) of all accidents were caused by an unsafe act by the person, with a smaller portion attributed to unsafe conditions. While modern safety science has refined this view – moving the focus from ‘who’ to ‘why’ – the concept of the unsafe act remains central to understanding the base of the Heinrich triangle theory of safety.

Understanding unsafe acts and unsafe conditions

An unsafe act is an action or behaviour that deviates from a standard job procedure or common sense, potentially creating a hazardous condition. Examples include failing to wear personal protective equipment (PPE), bypassing a safety guard, or using equipment incorrectly. Asking what is an unsafe act helps us define the scope of risk at the operational level.

Conversely, unsafe conditions are the physical, environmental, or system faults that increase the likelihood of an accident. These include faulty equipment, poor lighting, a cluttered workspace, or, crucially, an inadequate procedure.

Modern safety philosophy recognises that most unsafe acts are a logical consequence of unsafe conditions and vice versa.

For instance, an employee taking a shortcut (unsafe act) is often doing so because of pressure or a poorly designed process (unsafe condition).

Leveraging Behaviour Based Safety at the Base of a Safety Triangle

This is where the link to behaviour based safety is strongest. A robust behavioral safety programme uses systems like a bbs observation to proactively look for these unsafe acts and unsafe conditions. Instead of waiting for an incident, we observe current safety behaviour observation patterns and intervene constructively.

By encouraging employees to conduct a safety behaviour observation and record it as part of their daily routine, organisations can collect vast amounts of data related to unsafe act unsafe condition near miss events.

This data populates the base of the Heinrich triangle, making the invisible risks visible. This method also involves the workforce directly, which is crucial for fostering a sustainable H&S culture.

Hence, BBS in safety becomes a prime driver and success is measured by the reduction in these observed unsafe acts, thereby shrinking the entire safety pyramid.

From unsafe acts and unsafe conditions to Proactive Safety

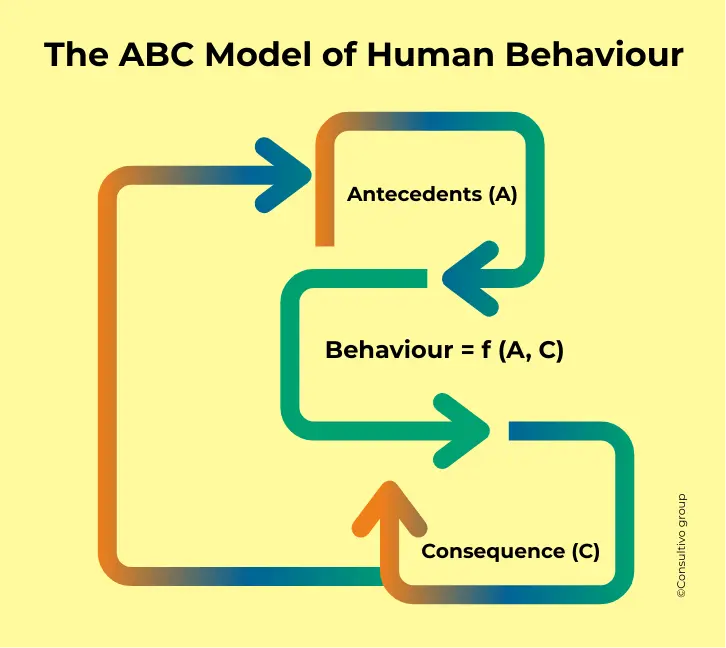

The goal is not to punish the unsafe act but to understand the unsafe condition that allowed it. If safety surveys or bbs observations show that workers often skip a crucial step, the question is: Why?

- Is it a Job Factor? (e.g., confusing procedure, lack of time)

- Is it a Person Factor? (e.g., fatigue, poor training)

- Is it an Organisation Factor? (e.g., production pressure, poor supervision)

These are known as Performance Influencing Factors (PIFs), which directly relate to the EPCs (Error Producing Conditions) used in human error assessment techniques. Therefore, the modern application of the Heinrich accident triangle is to use data from the base (near misses and unsafe acts) to drive changes in the system to eliminate the unsafe condition. This approach creates a healthy safety work culture based on trust and continuous improvement.

Explore our blog: The HEART Technique: A Simple Guide to Human Error Assessment

Expanding the Theory: Bird’s Pyramid and the Modern View

While H.W. Heinrich laid the groundwork, the safety pyramid concept has evolved, primarily through the influential work of Frank E. Bird and the integration of human factors science.

Frank E. Bird’s Expansion: Strengthening the Accident Pyramid

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Frank E. Bird, of the International Loss Control Institute, significantly expanded on Heinrich’s original work. Bird studied 1.7 million accident reports from nearly 300 companies worldwide – a much larger and more scientifically diverse data set than Heinrich’s. This expansion gave the theory new statistical weight.

Bird presented his own updated ratio, which refined the Heinrich pyramid theory figures:

- 1 Serious Injury

- 10 Minor Injuries

- 30 Property-Damage Incidents

- 600 Near Misses

Bird’s version strengthened Heinrich’s core argument: focusing on near misses and unsafe acts prevents major incidents. It also introduced the idea that incident outcomes vary (injury vs. damage), but the underlying behavioural and system causes at the base are often similar.

Bird’s work cemented the accident pyramid as the leading model for proactive incident control and further validated the need for comprehensive near-miss reporting.

Later, he established that human intervention could predict and prevent most accidents.

During this time, this concept also became popularly known as the injury pyramid.

The Human Element of Heinrich’s Triangle: Integrating Human Factors and Human Error Assessment

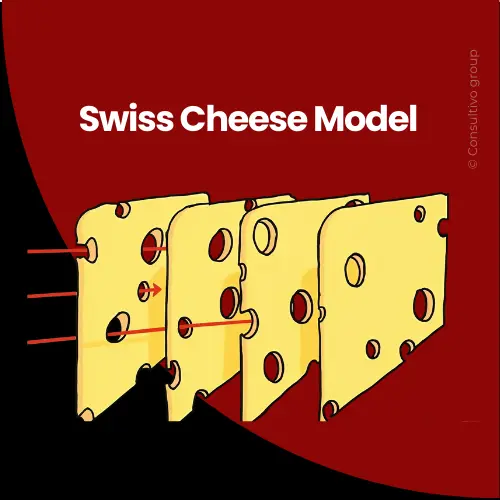

Around the same time, the field of Human Reliability Analysis was developing. Experts like A. D. Swain and later James Reason (with his Swiss Cheese Model) focused on how human error affects complex systems. This research, widely embraced by safety professionals, highlighted that:

- Most errors result from system design, task complexity, and organisational factors, not just individual carelessness.

- Human performance varies depending on training, workload, stress, and environment.

Swain’s and Reason’s work expanded the picture by showing that an unsafe act often reflects deeper system issues, or unsafe conditions, not purely individual action. This understanding shifted the primary goal from blaming human failure to managing it. This holistic approach is essential for any modern safety work culture.

Techniques like the Human Error Assessment and Reduction Technique (HEART) are now used as advanced tools for human error assessment. HEART helps us identify the human error influencing behaviour by systematically analysing Performance Influencing Factors (PIFs) and designing better systems to stop these errors before they cause harm.

HEART is a simple, powerful framework for understanding and preventing mistakes that moves beyond the simple counting of the Heinrich safety pyramid theory.

Practical Strategies for Leveraging the Heinrich’s Triangle Today

The enduring value of Heinrich’s triangle lies in its practical application. It serves as a visual mandate for where safety resources should be directed: the broad base.

Focusing on the Base: Near Miss and bbs observation Reporting

For the safety pyramid to work, the base must be accurately measured. Under-reporting of near misses and minor incidents is the biggest threat to this model.

Encourage Robust Near-Miss Reporting:

- Remove the Fear: Management must create a culture where reporting a mistake or a hazard is celebrated, not punished. This is a crucial element of a strong H&S culture. Employees must feel comfortable reporting unsafe act unsafe condition near miss without fear of reprisal.

- Keep it Simple: The reporting process should be quick, anonymous (where appropriate), and accessible (e.g., via a mobile app). A complicated process leads to non-compliance.

- Feedback Loop: Always provide feedback on what action was taken based on a report. This validates the effort and encourages further reporting, sustaining the safety work culture.

Implement Structured BBS Observation:

- A formal behaviour based safety programme, including structured safety behaviour observation, provides the most consistent data on unsafe acts.

- Train supervisors and peer observers to look for specific, critical unsafe acts and unsafe conditions. They are looking to identify what is an unsafe act and why it is happening.

- The data collected through bbs observation and safety surveys must be trended against the Heinrich triangle to show that increased proactive effort at the base reduces incidents at the apex.

Building a Strong safety work culture and Management System

The Heinrich pyramid safety model cannot exist in a vacuum; it must be supported by a strong organisational structure.

Leadership Commitment:

- Senior management must champion the Heinrich triangle philosophy. Safety success should be measured by the number of resolved near misses (proactive indicator), not just the low number of accidents (lagging indicator).

- Visible commitment to safety sends a powerful message that production targets will never override the need to address an unsafe act or unsafe condition.

Comprehensive Risk Management:

- Ensure that all Heinrich accident pyramid layers are addressed in your risk process. A near miss (base) should trigger a root cause investigation similar to a major accident (apex), just on a smaller scale.

- Regularly use safety surveys to assess the organisational factors that create unsafe conditions, such as fatigue, high workload, and communication issues.

Training and Competence:

- Training must go beyond basic compliance. It should help employees understand the why – the principles of the safety triangle – and how their actions contribute to the overall H&S culture.

- This is fundamental to reducing unsafe acts; workers must be fully competent to deal with the task and environment.

Future Trends: Beyond the Traditional Heinrich’s Safety Triangle

Modern research has both strengthened and challenged aspects of the safety triangle.

While the ratios (like 1:29:300) may not be universally exact across all industries, the core concept remains undisputed: frequent minor events predict severe ones.

Behavioural Safety and Culture

The focus on behavioural safety is the natural evolution of the Heinrich triangle. This field uses the Heinrich triangle of safety as its logical proof. Why? Because the most efficient way to influence the base of the triangle is by focusing on observed behaviour and the underlying unsafe conditions that drive it.

Organisations are increasingly recognising the importance of understanding the behaviours and attitudes that contribute to unsafe practices. By addressing these factors through specific training, awareness programmes, and behavior based safety initiatives, organisations can create a sustainable H&S culture and encourage employees to adopt safer practices.

The data from bbs in safety programmes is the essential fuel that keeps the safety pyramid functional.

The link between a strong safety work culture and the Heinrich triangle is direct:

- Strong safety culture = Fewer unsafe behaviours, better reporting of near misses, and early identification of risks.

- Weak safety culture = High frequency of unsafe acts, under-reporting of incidents, and a reactive, chaotic response to major events.

The Role of Technology and Human Error Assessment in Heinrich’s Triangle

The future of the Heinrich triangle lies in technology and better human error assessment. Advanced data analytics tools can now help organisations identify patterns and trends in incident data faster than ever before.

This moves beyond simple counting and helps pinpoint specific locations or tasks with a high unsafe act unsafe condition near miss rate.

The use of AI and predictive analytics is allowing us to move from simply recording Heinrich triangle data to predicting where the next incident is likely to occur.

For example, sensors and wearable technology can provide real-time monitoring of job factors (like poor environment or fatigue), which are key PIFs/EPCs. This allows safety teams to intervene before the unsafe act even occurs, thereby proactively cutting off the base of the accident triangle entirely.

The Heinrich triangle remains a powerful teaching tool and a foundational benchmark. However, it must always be applied within a holistic safety work culture framework, integrating technology and a deep understanding of human factors, to ensure the long-term effectiveness of incident prevention.

Start your bbs safety journey today

Safety Culture Transformation

Solution Areas

Related Blogs

Let's discuss

Share this post

Category: Blog

About the author

CEO and Chief Mentor of Consultivo

Saikat Basu is an experienced strategic and operational risk management professional with a strong global track record in ESG consulting, auditing, and training. Passionate about capacity building, he has delivered numerous programmes across sectors, helping organisations strengthen safety, sustainability, and responsible business performance.

He is the principal architect and co-creator of Consultivo’s SMILe Safety Culture Transformation Framework, integrating behavioural science with practical organisational change. Saikat has worked with 200+ international and national standards in ESG, safety, and sustainability assurance.

He serves as a jury member for leading SHE, Environment, and Social Impact awards, and is a visiting faculty at various academic and industry platforms. A committed writer and thought leader, Saikat regularly contributes insights on safety culture, behavioural safety, ESG, risk management and responsible business.

Related insights

View more in Impact Stories | Blogs | Knowledge Bank | News and Events